As companies throughout the U.S. and the world race to develop new technology to make life in cities safer and easier, citizens’ attitudes ebb and flow with the headlines. Data collection, autonomous vehicles, smart city infrastructure—ideas like these often toe the line between utopian and dystopian future ideals.

We are fortunate to be witnessing a unique point in human development, presented with an opportunity to design our world in hyper-specific ways to meet our needs. Cities are getting smarter. Some restaurants, coffee shops, and retail stores have gone completely cashless. A city built on a foundation of connectivity and mobility has the potential to become something truly incredible. But how do we get to that point of innovation? Where do we even start?

What does it mean to be a person in a modern city?

The first step in understanding how we begin to form a smart city is with a basic, if slightly existential, set of questions: What does it mean to be a person in a modern city? What matters most? What is holding us back? If we were to survey people living in the U.S., we’d likely receive a wide variety of answers. Being a person in a modern city may boil down to being connected or feeling safe. A list of what matters most would likely include traffic and mobility, safety, security, the environment, homelessness, and cost of living. We might identify what is holding us back as bureaucracy or, ironically, lack of communication.

Innovators are tasked with the responsibility of balancing the variability of our priorities with the questions that smart cities pose. Thankfully, many of these issues can be addressed with smart city technology. The truth is that many of our problems exist because our cities were not built with interconnectivity in mind, even in a country as young as the United States. Our world and the way we communicate has changed dramatically just in the past 20, 30, and 50 years.

iot.telefonica.com

iot.telefonica.com

Focus on the data and what we know already

The foundation of any smart city project must begin with secure data collection and sharing. When the City of Atlanta recently had their entire digital infrastructure held hostage by hackers, we got a startling glimpse of our own vulnerability. Facebook’s data breach proves that even tech behemoths are susceptible to data theft. And yet, we need meaningful partnerships between technology companies and city governments in order to make innovation possible.

We already have numerous smart city prototypes to learn from. Songdo in South Korea, Quayside in Toronto, and most recently Union Point in Massachusetts are all cities built from the ground up with interconnectivity in mind. These cities can teach us valuable lessons about what works and what doesn’t work, so that every smart city need not start from scratch. We also know that we’re already living in the future; it would have been hard to predict the popularity of Uber or Airbnb 10 years ago. Now, it’s hard to imagine city life without them. We might have scoffed at the idea of Facebook becoming ubiquitous 15 years ago, and yet here we are. We know that through the Internet of Things, city life has the potential to look as different as we can possibly imagine in a very short span of time.

Innovation through public-private partnerships and the future of urban mobility

Municipalities function bureaucratically, and, as a result, are not an ideal mechanism for innovation. Tech companies, on the other hand, are designed to think futuristically and are often willing to take risks in ways that city governments simply cannot. Cities throughout the world are beginning to implement basic smart technology, but only because of the research and strategies developed by private companies.

Most modern cities in the U.S. are designed with cars rather than people in mind. In LA alone, 14% of the city is dedicated to parking and there are over 3 spaces per registered car in the city. Yet, even with this surplus, it takes the average driver 12 minutes to find a place to park. In Houston, Texas, there are 30 parking spaces for every resident. Although many residents living in both city centers and suburbs consider cars essential, the average car spends 95% of its life parked.

The first solution posed—car sharing—has been around for years, most recognizably in the form of Zipcar, and recently Maven and Turo. But these services seem to be the answer to sporadic long-distance driving, rather than day-to-day personal vehicle needs. Even a person who drives to work daily has a car that lives the majority of its life in a garage. The real solution to urban mobility would have to fall somewhere between cars for hire and public transportation. In other words, the real solution is autonomous vehicles.

The freedom of driverless cars

According to a 2014 Pew Research study, roughly two-thirds of Americans expect most cars to be autonomous in the next 50 years. Of course, we know that autonomous vehicles will bring an entirely new set of problems (and solutions) related to urban mobility: the reduction in traffic fatalities versus the major source of organ donations, reduced traffic violations versus the major source of revenue for many cities, and the gradual surplus of private and public parking spaces.

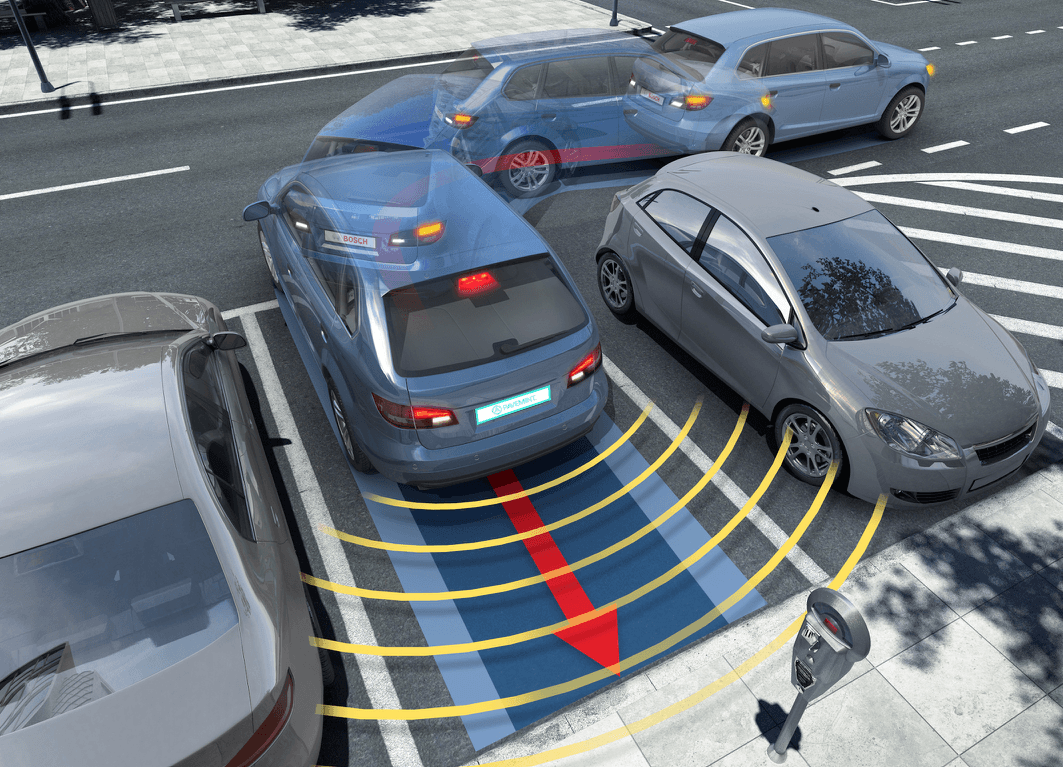

Partnerships between cities, tech companies, and private companies will help to mitigate the inevitably awkward shift towards smart cities, and especially the transition from personal vehicle ownership to autonomous vehicle ownership. Although autonomous vehicles will come equipped with sensors to measure environmental factors, require less space to store, and offer countless other features, this doesn’t solve parking difficulties.

Companies like Pavemint, a peer-to-peer parking app, will play a major role by maximizing existing parking and making it available through smart technology. Even as city governments reduce and eventually eliminate parking minimums, most American cities were designed with car ownership rather than shared transportation in mind. As a result, Pavemint, which allows users to both rent out and reserve parking on private property, stands to transform residential and business parking into short-term storage for autonomous and commercial vehicles. By freeing up the curbside, Pavemint will allow for more efficient urban mobility and help autonomous vehicles become the ultimate last mile solution.

Once we quantify and organize the existing space for resources, we gain the freedom to unlock and repurpose what remains. It will be that much easier to come to a consensus about what is no longer necessary, so that the large swaths of paved space we’ve accepted in our urban centers can be reimagined as green space, affordable housing, and more.

What do we want in an American smart city? It’s simple, really. We want to feel connected, mobile, accessible—to know that we are protecting the environment, living sustainably, and leaving the world a better place for future generations.